Canyon de Chelly

In the vast red desert landscape of Arizona, in the same state as the Grand Canyon and Monument Valley, there is a virtually unknown canyon that is comparable in beauty to these two famous national parks.

I am referring to Canyon de Chelly (pronounced Canyon de Shay), which is unique among National Parks, as it is comprised entirely of a Navajo Tribal Land Trust that remains home to their canyon community.

Before beginning to plan our three week RV Adventure, I had never even heard of this place.

The name Chelly is a Spanish term which borrowed the Navajo word Tséyiʼ, which means “rock canyon” (literally “inside the rock”). It is one of the longest continuously inhabited landscapes of North America and preserves the ruins of the indigenous tribes that lived in the area, from the Ancestral Puebloans (also known as the Anasazi) to the Navajo.

I had never heard of the term Anasazi until we visited Mesa Verde a couple of days ago. The benefits of going travel to places you’ve never been.

To this day, the canyon sustains a living community of Navajo people, who are connected to this landscape. People have lived in these canyons for nearly 5,000 years – longer than anyone has lived uninterrupted anywhere on the Colorado Plateau.

The National Park covers 83,840 acres and encompasses the floors and rims of the three major canyons: Canyon de Chelly, Canyon del Muerto, and Monument Canyon.

Once you arrive in the park, you can explore the edges of the canyon first if you like. We did. There are a series of ten outlook points with spectacular views that stretch across South Rim Drive and North Rim Drive. When we first arrived we thought that would be the best way to see the entire park before we got down to some hiking. We were here to hike the White House Trail and do some horseback riding in the canyon.

Spider Rock Campground

Before I begin talking about our hike and the canyon, I wanted to talk a bit about our RV Park in Canyon de Chelly – Spider Rock Campground. It is inside the park and operated by the Navajo. Our host there was Howard Smith, who is a native Navajo born of the Todachine’ clan for the Tacheenie clan, and is of the people of the Tsegi area of Canyon de Chelly.

He was raised in the area of Spider Rock Campground and grew up herding sheep throughout the canyon, along the south rim and at the canyon bottom.

Howard has now opened his home to visitors by creating this campground and enjoys sharing his knowledge with the many people that come to stay in his campground. That knowledge potentially saved my life.

I was impressed with the canyon and wanted to take some photos at sunrise but the hike to the rim of the canyon was about a quarter mile from where we had parked the RV and I wasn’t feeling that confident so one evening, I went over to talk with Howard. I asked him if he knew a good trail I could take to the canyon just before sunrise. He answered slowly but the message was very clear in what he was saying. He said, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you. There are mountain lions all around the rim of the canyon and walking through the woods just before daybreak doesn’t sound like a good idea to me”.

As you may have guessed, this travel post will not contain any sunrise photos.

The White House Trail

There are several dozen paths into the three main ravines in Canyon de Chelly National Monument, all ancient Navajo routes which have been in use for centuries, but only one is open to unaccompanied hikers – this is the White House Trail, which descends nearly 600 feet down the cliffs on the south side of Canyon de Chelly, crosses the seasonal Chinle Wash and ends beside one of the most famous ancient dwellings in the monument, a two-level structure with one part on the valley floor and the other 50 feet up in an alcove.

All other paths in the monument require permits and guides; there are approximately 14 such routes, along either the south side of Canyon de Chelly or the north side of Canyon del Muerto.

The White House Ruin Trail begins at an overlook at the end of a short spur road, 7 miles east of Chinle. For those not hiking the trail, a walk of just 350 feet reaches the overlook, which has a good view of the ruins, 2,000 feet east, plus another, smaller structure nearly opposite. Typical round trip times for the trail are 1 to 2 hours, and the path is wide, well-used and not too steep. We spent close to five hours down there…

NOTE: White House Trail has been closed to the public since March 2020.

The trail starts off due south, running along the canyon edge for a short distance then dropping below the rim, down the uppermost section of the cliffs, to a bench, followed by a short series of switchbacks descending a boulder-covered slope, close to bigger cliffs to the north. The final switchback curves around a slick rock bowl, the lowest segment of the main cliffs, and ahead the land is more gently sloping, and sandy.

The trail then moves northwards, descending into a little ravine, passing at two points through short tunnels, and emerging to the flat land beside Chinle Wash. Near the lower end, just before the second tunnel, the path takes an interesting short-cut down a narrow gully, using old foot-holes carved in the sandstone walls.

Chiseled by millions of years of stream-cutting and land uplifts, the colourful sheer cliffs of Canyon de Chelly National Monument may look harsh and barren, yet in fact, natural water sources and rich soil make them anything but. These canyons have supported human inhabitants for thousands of years, from the Ancient Puebloans who planted crops and raised families here 5,000 years ago to their descendants — the Hopi people — who cultivated peach orchards and cornfields among the cliffs.

The Navajo — also known as the Dine — settled in the region much later, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument continues to be a protected land for Navajo people and their culture. The park was established in 1931, largely to preserve its rich archaeological sites, and to this day, the homes and farms of the Navajo are visible from the clifftops.

The Canyon Floor

On the valley floor, a huge protruding rock rises 560 feet directly ahead, inside a U-bend along the wash, while to the south is a line of trees and a sizeable cultivated area. This has fences, fields, an orchard and a hogan, but all is off-limits to hikers, and a sign directs people away to the north, along the base of cliffs which soon become very tall and sheer.

The path then crosses the wash on a footbridge and follows the east bank for a quarter of a mile to the ruins. Once at the White House, rest rooms and Indian jewelry sellers detract a little from the experience but the delicate well-preserved buildings beneath the sheer, desert varnish-streaked, cliff are well worth the trip.

Being down in the canyon really changes the dynamic of what these walls actually look like.

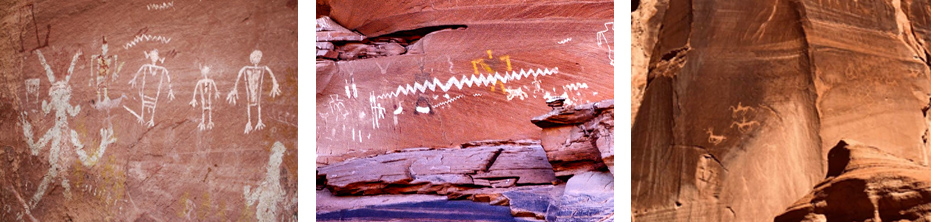

Desert Varnish, the dark red and black streaks on the canyon walls, are thousands of years in the making. The streaks are created through the oxidation of manganese and iron, usually where water runs down the canyon walls. The black varnish has a higher content of manganese while the red and dark brown varnish is rich in iron.

The Navajo People have traditionally collected the black varnish and added the minerals to their soap and shampoo. It is told that if you wash your hair with desert varnish, you’ll have long, healthy hair.

The White House Ruins

Construction of the buildings at the White House site began around 1070, and the place is thought to have been abandoned in the late 1300s. The name derives from a whitish band across the nearby cliffs. The lower ruin, on the canyon floor, once comprised around 60 rooms, while the upper, alcove site has 20, including four kivas. Together, the dwellings were home to at least 50 people.

Only around half of the lower ruin is visible today; the remainder was washed away as a result of several years of unusually high rainfall in the 1910’s.

Excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries revealed burial sites, tools, projectile points and large amounts of pottery including several complete items.

Horseback Riding through the Canyon

One of the things Yim wanted to do more than anything once I told her that there were horseback riding options at Canyon de Chelly was to take one, so we booked a 3 hour ride with Justins. Justin Tso and his crew have been taking riders into the canyon for 25 years.

It was a fantastic decision.

We found Justins located in a turn on the road just as you enter the park and headed down a dirt road to a wooden structure. It was pretty laid back and we parked the RV as un-obstructively as we could and wandered over to meet the staff. They were pleasant enough but very soft spoken and we were led to the two small Mustangs we would be riding and introduced to our guide, whom I have forgotten his name now. My bad.

Yim and I each mounted our little Mustangs and followed our Navajo guide into this land that time has truly ignored. A small dog followed us, staying close behind our guide and we headed off into the canyon.

The canyon barely exists at the mouth of the wash. The rim is virtually at ground level on the south side, and it’s only fifteen or twenty feet tall on the north side—but that aspect changes pretty quickly as you travel upstream. The canyon walls rise dramatically on both sides, and in what seems no time at all, they’re soaring high overhead.

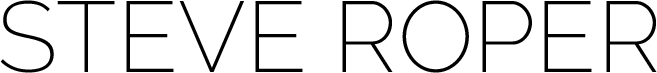

About an hour in we came across the first set of petroglyphs on the walls. Art rendered by generations of canyon dwellers includes ancient carvings of Kokopelli (a mischievous flute-playing deity), cave ceilings decorated with charcoal depictions of constellations, and vividly coloured, richly detailed hunting scenes painted after the Spanish brought horses to the canyon in the 17th century.

By the halfway point, we had passed homesteads with gardens, a river which seemed to be properly utilized around the homes within the canyon for irrigation purposes, small herds of sheep, a few wild horses and children out playing in their yards, all surrounded by 300 foot walls teeming with history. We got off our Mustangs for a break and tied them up in the shade of a Cottonwood tree and sat for a bit. Our guide was very quiet spoken and answered all of our curious questions, which I was certain he had heard hundreds of time.

After a while, we got back on our horses and Yim and I rode side by side for an hour as we clip-clopped along in the sand. The little dog close behind us still. It was so quiet.

Three hours later, we were back where we started, said our goodbyes and headed back to Spider Campground and prepared to visit Spider Rock (photo below), hoping to catch a sunset. We did.

Spider Rock

According to Navajo legend, Spider Woman lives at Spider Rock in Canyon De Chelly. She was first to weave the web of the universe. She taught the Navajo how to weave, how to create beauty in their own life and to spread the “Beauty Way” teaching of balance within the mind, body & soul.

Spider Rock, which was named for Spider Woman, rises more than 700 feet from the floor of the canyon.

I did a bit of research and found that Spider Rock is the last remnant of the stream and hill slope erosion process that continues to make the canyons deeper and wider to this day. Spider Rock at one time (many thousands to perhaps even hundreds of thousands of years ago) was connected to the ridge between the main Canyon de Chelly and Monument Canyon. The hill slope and stream erosion processes worked at different rates along that ridge, obviously at a slower rate right at Spider Rock. The differential erosion left this tower that is now called Spider Rock behind.

Eventually, Spider Rock will topple, as have other rock monoliths in the national monument.

For now, though — and likely for centuries to come — it’s a highlight of any visit to Canyon de Chelly.

But if you are reading this, I suggest you go as soon as possible.

No Comments